Baby boomers: Retired, homeless

It’s starting. The baby boomers – all 79 million of them – are beginning to retire. Many of the oldest boomers, in their late 50s and 60s, are facing important housing decisions: move to a cabin up north or golf community down south?

Other boomers aren’t as fortunate. They have a more difficult question to answer: What happens when you’re too old to work, but you don’t have money for a place to live?

The result can be homelessness, a reality The Salvation Army sees every day. Retirees like 66-year-old Cindy D. walk through our doors wondering what they’re supposed to do without food, money or shelter.

“I’ve never been homeless before,” Cindy said, while waiting in line for a bed at The Salvation Army Harbor Light Shelter in Minneapolis. “I look like someone who used to have a pretty nice life – and I did.”

The Twin Cities Salvation Army shelters hundreds of aging boomers like Cindy at our three local housing facilities – Harbor Light, Booth Manor and HOPE Harbor. Similar facilities are in Mankato, Rochester and St. Cloud. (View photos of all six facilities.)

“The number of low-income baby boomers in need of affordable housing is set to explode in the next decade and beyond,” said Major Jeff Strickler, Twin Cities Salvation Army Commander. “The housing facilities and programs we have in place will be more important than ever to the low-income aging population in the years ahead.”

Ella Davison, 70, has lived in Salvation Army housing in Minneapolis since 2004, paying with a portion of her pension. “The Salvation Army is God’s protection,” she said.

Harbor Light

In the heart of downtown Minneapolis lies Harbor Light, the state’s largest homeless outreach facility. As many as 675 people, many of them ages 50 and older, sleep in the six-story building every night. The facility also serves hundreds of free hot meals and offers a wealth of rehabilitation and social services programs.

Harbor Light is mainly geared toward providing emergency shelter, though people like Cindy D. often stay for extended periods. By spring 2013, Cindy had been sleeping at Harbor Light almost every night for six months. She became homeless in June 2012 and spent the summer sleeping in local parks. Until then, she lived in her own apartment and received $1,200 per month via her late husband’s pension.

“Now all of that money is spoken for – I got in over my head with the credit cards and messed up,” said Cindy, who occupies her time by reading books at the library. “But I don’t feel sorry for myself. I made my life what it is.”

Cindy planned to file for bankruptcy. If successful, she’d be able to re-collect the pension and find a home.

“I can still make myself laugh – you have to,” said a smiling Cindy, who became known as “Grandma” to Harbor Light regulars.

In addition to providing emergency shelter, Harbor Light also helps people find permanent homes. In the past four years, Harbor Light caseworkers have found independent and supportive housing for more than 1,000 men and women.

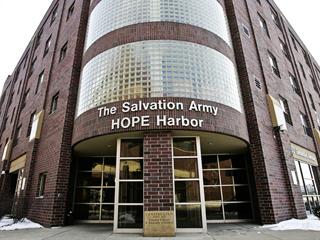

HOPE Harbor

HOPE Harbor

Next door to Harbor Light is HOPE Harbor, a 96-unit supportive housing complex for low-income single adults and the chronically homeless. Each unit is an efficiency apartment complete with kitchen and bathroom. The five-story facility includes offices where case managers help residents with job searching, spiritual enrichment, addiction counseling, medical needs, budgeting, life skills and more.

Though most residents stay a few years, others like Fannie Mae Anderson (pictured at top), 68, stick around longer. She moved in nine years ago after arriving in Minneapolis from Chicago to live with her daughter. Unfortunately, the two couldn’t get along, and Fannie ended up in a transitional shelter for six months until she was referred to HOPE Harbor in June 2004.

“They treat you so nice here – they’re really good to you,” said Fannie, who spends her spare time volunteering and cooking her two favorite dishes – sweet potato pie and macaroni and cheese.

Most HOPE Harbor residents pay rent based on a sliding scale equal to a third of their income. Fannie, for example, pays just over $200 per month based on her monthly social security income of around $600. Those unable to pay anything stay for free.

If not for HOPE Harbor, Fannie and other aging boomers like her would have few options.

“Without housing, people can cycle in and out of shelters, detox, jail or hospital beds,” Strickler said. “That can cost taxpayers thousands of dollars per month. Yet for that same monthly cost, The Salvation Army can give someone a safe home for many months or even an entire year.”

Booth Manor

Booth Manor

Believe it or not, The Salvation Army has an entire high-rise devoted to aging boomers – Booth Manor. The 21-story complex, located in Minneapolis next to beautiful Loring Park, includes 165 one-bedroom apartments for seniors ages 62 and older.

With its incredible location and large living units, Booth Manor is like an “upscale” version of HOPE Harbor. About a third of the residents pay market-rate rent of $500 to $600 per month; the rest are subsidized by HUD or other assistance programs. All can stay as long as they’d like.

Eva K., 66, moved to Booth Manor during summer 2012 after living at HOPE Harbor for 18 months. She says both facilities have been a godsend considering her circumstances: she’s a wheelchair-bound, ex-convict with nowhere else to live.

“I was turned down by so many places,” Eva said, reflecting on how challenging it was to find housing after she was released from prison, doing 13 years of time for drug-related crimes. “I don’t have a pretty past. But The Salvation Army gave me a home and hope. I’m so thankful.”

Aside from living in a beautiful place she can afford, Eva enjoys some of the other things Booth Manor offers: Bible studies, grocery outings, educational speakers, birthday parties, monthly food banks and much more.

Outstate Minnesota

The Salvation Army operates additional housing facilities in outstate Minnesota, all of which are regularly utilized by baby boomers.

- Mankato: Two facilities: A 10-unit supportive apartment complex for homeless single adults and a winter emergency shelter for up to 23 men.

- Rochester: A 32-unit supportive housing facility similar to HOPE Harbor.

- St. Cloud: A 24-hour shelter for up to 65 people. Similar to Harbor Light.

In addition, The Salvation Army operates nearly 100 transitional and permanent housing units in Duluth, the Twin Cities metro area, Rochester and Willmar. Most are rented apartments or homes. All include case management support.

“There are many challenges ahead in providing an adequate amount of affordable housing for aging baby boomers,” Strickler said. “The Salvation Army is poised to help meet these challenges through our existing housing facilities, innovative programs and loyal donors.”